I believe open source is the way to go. It takes control from big tech and puts it back in your hands. From building my sync system without Google Drive or OneDrive to replacing Google services with open source alternatives, I’ve consciously made a shift to using open source.

The more open source I go, the more I experience control, transparency, and freedom. However, going fully open source is a different challenge.

However, I hit a wall that exposed how daunting this undertaking was. I’m not talking about the general issues in the open-source space—lack of user-friendliness, poor documentation, and inconsistent maintenance or development. I’m referring to the personal challenges and bottlenecks of completely going open-source.

Control isn’t always connection

The illusion of control when you first go all-in on open source

When I moved entirely to open source, everything looked perfect. I was syncing my files across devices using Syncthing; I had built out my notes on Joplin, and had Nextcloud running on Linux Mint on an old computer. This setup meant no hidden analytics or silent updates. It was my system, my rules.

But when reality hit me was when I needed to share files outside my open source configuration. I had a friend who needed access to a certain folder, and there was also a teammate who wanted a quick file. All of a sudden, this freedom I was enjoying became a maze of links, permissions, and the hardest of all, explanations.

Syncthing, for instance, is a peer-to-peer sync tool, and it requires the recipient to also install the app. With Nextcloud, I had to generate a public link, set an expiry date, and often add a password. On top of that, I had to verbally explain how to use the link—where to enter the password and how it differs from clicking a Dropbox or Google Drive link. I had gained so much control but also felt less connected to everyone else.

It then hit me that control is easier when you’re in isolation. You lose flexibility the moment your workflow involves someone who doesn’t run the same stack. What I had created was beautiful and private, but it was an island. Open source wasn’t failing me—I only assumed that independence also meant interoperability.

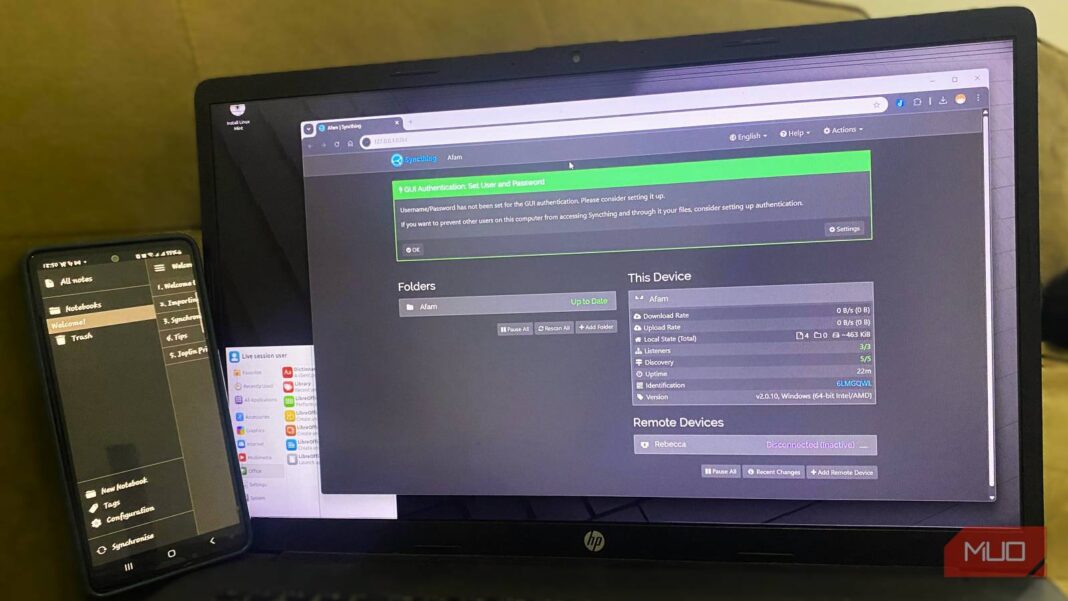

My phone became the weakest link

The open source dream can collapse in your pocket

My open-source setup was perfect on desktop, but the moment I tried the mobile services, the experience became less desirable. This is where it felt like mobile life belonged to mainstream and closed source.

The issue seems to be with how the tools fit into the platform. For instance, there are sync state problems syncing on the Nextcloud and Joplin mobile apps that occasionally result in duplicates. Android’s built-in battery manager may occasionally decide that these apps use too much power and close them in the background, meaning the syncs will fail as a result.

The peer-to-peer nature of Syncthing means both devices must be online to sync, and syncing across networks may require extra setup, such as enabling relays. This makes the idea of creating a note on my mobile device and instantly accessing it on my PC even harder.

Also, with some of these services, mobile notifications are often unreliable. I usually wouldn’t know when my Nextcloud updates are done unless I manually check. After doing these manual checks for a while, the phone starts feeling like a reluctant part of my workflow.

Sadly, these aren’t isolated to the few services I used as examples. When I use Thunderbird for Android, emails aren’t automatically fetched. So generally, while I love the desktop experience, for several of my go-to open-source tools, the dream of going totally open source becomes much harder to keep up with as soon as I use my mobile devices.

Control comes at a cost

Freedom is only real when it still lets you live

One of the walls I hit was the time I spent maintaining or upgrading my setup. For instance, there was a time I replaced Google Photos with Immich. Even though I set it to automatically sync from my mobile device, uploads would periodically stall because the app lost background permission or my phone entered sleep mode. Opening it manually and re-triggering uploads became more frequent than I’d like.

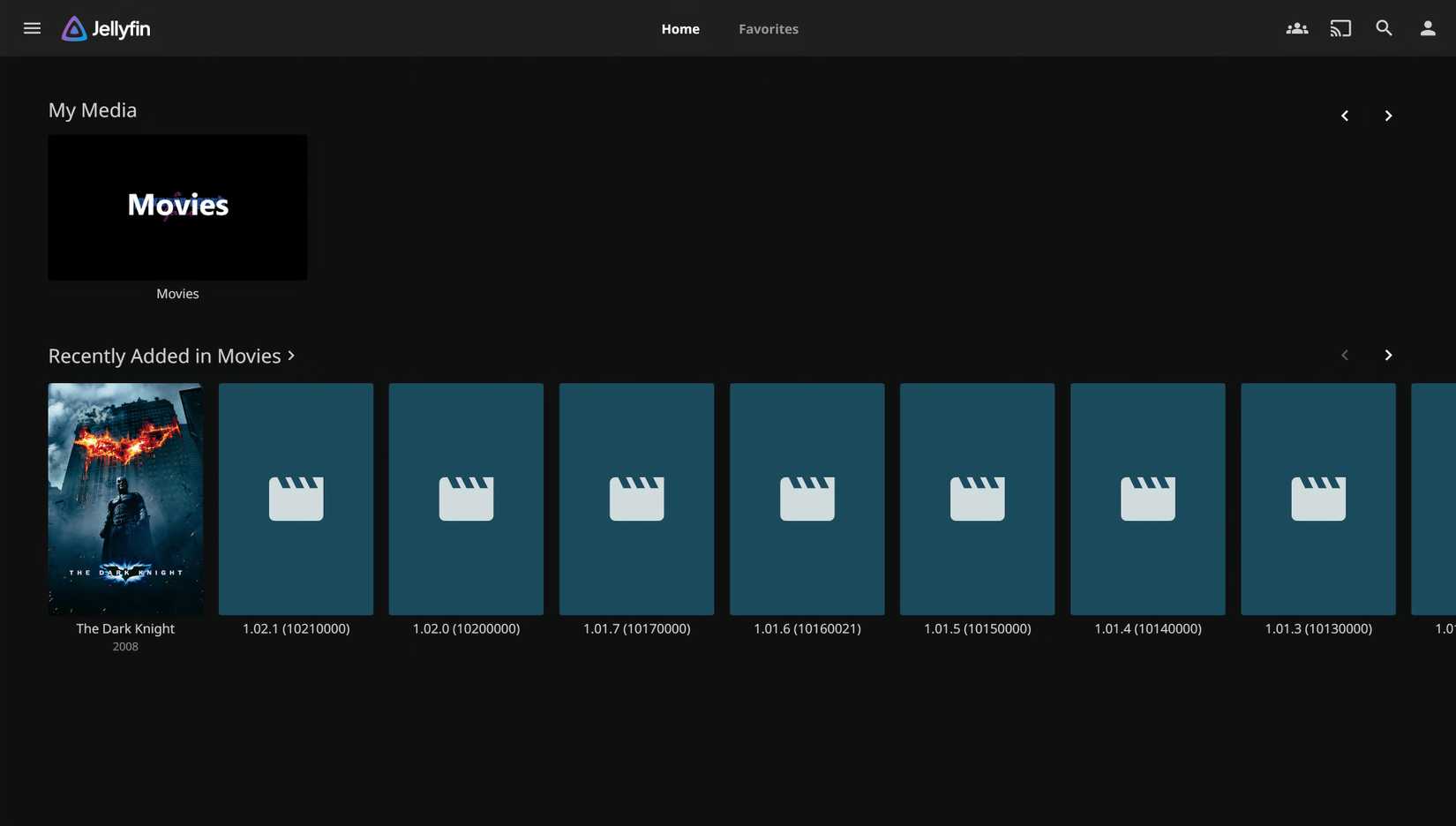

Also, when I started hosting my music library on Jellyfin, I realized the experience lags or fails if I stream outside my home network. I might hit play from the gym, and nothing happens, only because my home server went offline overnight.

Messaging was no exception. I first used Signal, and even though it worked well, the bulk of my contacts stayed elsewhere—WhatsApp or Facebook Messenger. It was exhausting bridging those worlds. Outside of managing servers, I now manage social logistics.

This level of upkeep affects the user experience and becomes an instant bottleneck if you choose to go entirely open source. There are so many services you need for your daily activities, and once you decide to go open source with all of them, you’ll spend more mornings than you imagined checking logs or restarting services.

Going fully open source is a project best left for the future

In the end, I wouldn’t recommend going entirely open source; it’s a good idea, but not the right time. Once you start using these tools in everyday life, you quickly realize several of the services aren’t yet as reliable as you’d hoped.

Open source has come a long way. Once upon a time, I could hardly keep my files synced across devices without constant errors or host my own media without glitches. Nextcloud, Syncthing, and Jellyfin are typically reliable for handling my files. As the space grows, I can see a point where going totally open source poses fewer bottlenecks.