I’m very fortunate to receive messages from readers and writers around the world telling me about books I might like to read. Many of the titles I’ve featured on this blog are the result of conversations with people in parts of the planet from which we English speakers rarely hear stories. Examples include: Glimmer of Hope, Glimmer of Flame, sent to me by Colin after a discussion with a bookseller at Libraria Dukagjini in Pristina, Kosovo; and The Golden Horse, the manuscript translation of which was emailed to me by author Juan David Morgan after it was recommended to me by the Panama Canal on Twitter. (Yes, really.)

Sometimes, however, I’m lucky to stumble across amazing stories from elsewhere closer to home. This latest Book of the month is a case in point: a few weeks ago, I spotted a new shop on the Old High Street near where I live in Folkestone, UK. It was, according to a sign in the window, a bookshop, gallery and publisher. Intrigued, I went inside and got talking to Goran Baba Ali, an author and co-founder of Afsana Press, which seeks to publish stories that have a direct relation to social, political or cultural issues in countries and communities around the world.

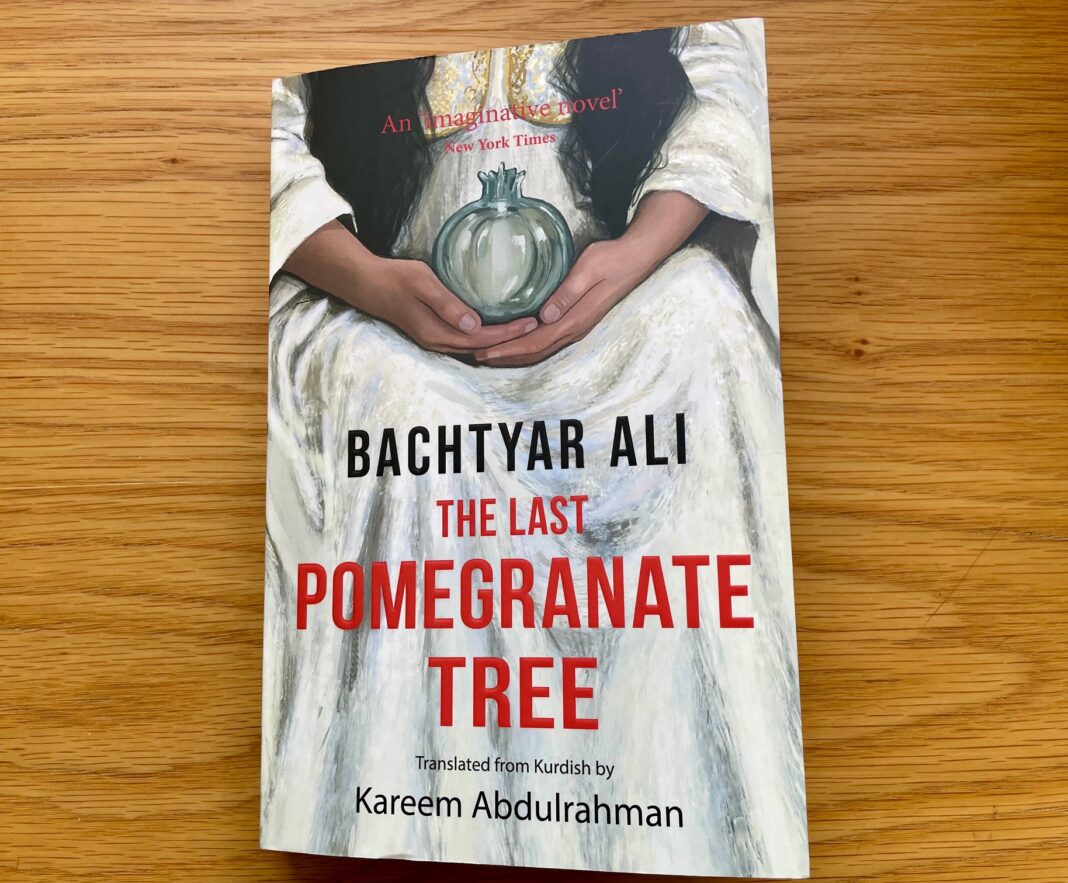

After a pleasant chat, I bought one of their titles, The Last Pomegranate Tree by Kurdish writer Bachtyar Ali, translated by Kareem Abdulrahman, and headed home. I was excited to read the book but also a little nervous. I really hoped it was good. It could be a little awkward the next time I bumped into Goran otherwise…

The novel begins with the release of 43-year-old peshmerga fighter Muzafar from a desert prison after 21 years. Yearning to reconnect with his son Saryas, who was only a few days old when Muzafar was arrested, he embarks on a quest to discover what happened to the boy. In so doing, he confronts the horrors visited upon his homeland and compatriots, the truth about love, loss and compassion, and what it means to be human.

Magical realism is a term I treat with some suspicion. In certain contexts, it can be used by critics to lump together and diminish anything in stories from elsewhere that doesn’t conform to certain Western norms. It is a term that has been applied to this book by some reviewers and I can see why: the story features many extraordinary creations and happenings. There is a character with a glass heart. There are women with hair that tumbles, Rapunzel-like, from windows down to the ground. The rules of the world are liable to tilt and twist. But in Ali’s hands, these happenings do not feel curious, exotic or strange, but rather expressions of deep truths, ‘that something always remained unexplained’, that when you live in a world where everything can be taken from you nothing is impossible.

One of the first things about this book that thrilled me (and there were many), was the beauty of the writing. Ali and Abdulrahman’s prose glitters with exquisite imagery. The pomegranate tree of the title stands on a mountaintop, ‘which rises up above the clouds like an island surrounded by silver waves’. Muzafar’s former friend Yaqub has ‘a strange gentleness in his words, as if you were standing near a waterfall and the wind was spraying the water towards you or you were asleep under a tree and the breeze had awoken you with a kiss’. Upon gaining his freedom, Muzafar ‘felt like a fish that had leapt back into the water from a fisherman’s net, its heart still filled with the recent shock of its probable death’.

This beautifully direct, expressive prose carries brilliant insights. Many of them centre on the enmeshment of humanity with all beings, ‘that the earth and life are a single interconnected whole’. Some reveal the mechanisms we use to deny this and insulate ourselves from others’ suffering. One of the sharpest examples of this is a passage in which a character advocating for the marginalised streetseller community is interviewed by a journalist:

‘That night by the fire, the journalist spoke about the wealth of agriculture and the yield of livestock, but Saryas spoke about the neglected and forgotten wealth of the thousands of abandoned children who found themselves on the streets from the age of four. The journalist talked about the charm of the cities, of clean pavements and the right of drivers to sufficient space for cars, but Saryas talked about the lost beauty of those children, himself included, who were forced to wash in filthy swamps because they had no access to clean water. The journalist argued for the return of the villagers to the countryside, Saryas for the return of people to a decent life.’

The writing is so powerful here. You can hear the conversation unfolding. The shift in register between the presentation of the two speakers’ statements shows us how they miss each other, the distance between them, and the way privilege and partisanship deafen those who imagine themselves openminded and fair.

Time marches to a beat that will be unfamiliar to some Western readers in this novel. Instead of the clockwatching chronology of many anglophone stories, there is a sense of a larger scope. A kind of deep time is at work, in which individual human destinies are only small parts of a much larger picture. ‘A person is a star that does not fall alone,’ reflects Muzafar. ‘Who knows where the echo will reverberate when we leave this earth? Perhaps someone will rise from our ashes in another time and realise they have been burned by the flame of our fall.’

The storytelling is similarly expansive. Over the course of the novel, it becomes clear that we readers are in the story too, cast as fellow refugees on a ferry Muzafar is taking to England in an effort to complete his quest. We are listening to Muzafar, whose account loops back on and contradicts itself, dented by his preoccupations and fears.

The effect is marvellous. This is honestly one of the best books I have read in a long time – so humane, so moving, so engrossing and so beautiful. To me, it is a reminder that we can find extraordinary, underrepresented voices anywhere. I live in a small town on the south coast of the UK and there is someone publishing world-class Kurdish literature a few minutes’ walk from my house.

The Last Pomegranate Tree by Bachtyar Ali, translated from the Kurdish by Kareem Abdulrahman (Afsana Press, 2025; US first edition Archipelago Books, 2023)