“Dance, dance… otherwise we are lost.” This oft-cited phrase by Pina Bausch encapsulates not only the urgency of movement, but its capacity to reveal space itself. In her choreographies, space is never a neutral backdrop, it becomes a partner, an obstacle, a memory. Floors tilt, chairs accumulate, walls oppress or liberate. These are architectural conditions, staged and contested through the body. What Bausch exposes — and what architecture often forgets — is that space is not simply built, it is performed. Her work invites architects to think not only in terms of materials and forms, but of gestures, relations, and rhythms. It suggests that architecture, like dance, is ultimately about how we inhabit, structure, and emotionally charge the spaces we move through.

Historically, architecture and dance have operated in parallel, shaping human experience through the body’s orientation in space and time. From the choreographed rituals of classical temples to the axial logics of Baroque palaces, built space has always implied movement. The Bauhaus took this further, as Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet visualized space as a geometric extension of the body. This was not scenery, but spatial thinking made kinetic. In the 20th century, choreographers like William Forsythe and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker integrated architectural constraints into their scores, while architects such as Steven Holl, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and Toyo Ito designed buildings that unfold as spatial sequences, inviting movement, drift, and delay.

This shared language is not only formal or aesthetic, but conceptual. Both architecture and dance are concerned with relation: between body and ground, interior and exterior, self and collective. Theorists such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Henri Lefebvre, and Susan Leigh Foster have shown how space is not merely occupied but produced through movement, rhythm, and perception. Today, as architecture confronts urgent questions of ecology, participation, and embodiment, revisiting dance as a critical interlocutor opens new pathways. To choreograph space is to conceive of architecture as an event, temporal, performative, and responsive, capable of staging encounters, rather than merely containing them.

Related Article

The Architect as Writer: Expanding the Discipline Beyond Buildings

An Architecture of Movement

The connection between architecture and dance is not a recent invention, but a historical continuum rooted in the organization of bodies in space. Since antiquity, architecture has been guided by bodily measurement and symbolic movement. Vitruvius placed the human figure at the center of spatial proportion, suggesting that buildings, like bodies, followed systems of balance and harmony. This ideal persisted into the Renaissance, when architects such as Alberti and Palladio sought to translate bodily order into geometric clarity. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man exemplifies this alignment: a drawing that does not simply illustrate proportion, but performs it — a figure whose outstretched limbs imply spatial reach, tension, and symmetry. In parallel, Renaissance dance formalized similar ideals: codified gestures, rhythms, and floor patterns that unfolded in spaces designed to mirror hierarchy and order.

But movement in architecture was never confined to ideal proportions or abstract drawings. Built space has always guided and staged physical motion through ritual, procession, and spatial sequencing. From the peristyles of Greek temples to the axial alignments of Baroque churches and palaces, built forms choreographed how bodies entered, paused, turned, and progressed. At Versailles, architecture and dance coalesced into instruments of political spectacle. Louis XIV, the “Sun King,” famously performed in ballets and constructed his palace as a theatre of power, where gardens, galleries, and ceremonial halls directed both sightlines and footwork. The palace became a stage, and its inhabitants, choreographed actors within a tightly scripted regime of appearances. Architecture here was not merely a container for movement; it encoded the movement itself.

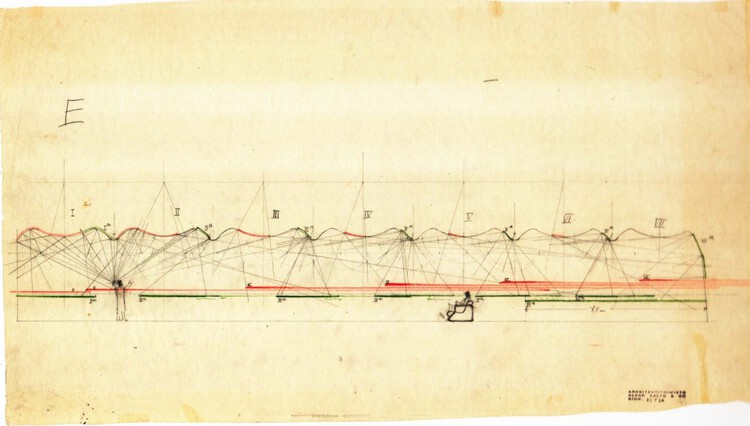

These choreographic logics did not disappear with the advent of modernism — they were reformulated. Le Corbusier’s promenade architecturale introduced a spatial dramaturgy based on bodily movement, arguing that architecture should be experienced as a sequence of orchestrated views and rhythms. At the same time, modern dance began to reject the rigidity of classical ballet, embracing groundedness, breath, and improvisation as expressive tools. Choreographers such as Rudolf Laban and Mary Wigman developed movement theories deeply attuned to space: Laban’s kinesphere offered a spatial model rooted in axis, reach, and orientation, while Wigman’s expressionist performances engaged with light, gravity, and asymmetry — elements echoed in the tectonics of early modernist buildings.

This shared rethinking of space found built form in designs such as Mies van der Rohe’s Tugendhat House, where the open plan operates like a stage, allowing the occupant’s body to define spatial boundaries through motion. Similarly, Alvar Aalto’s Viipuri Library introduced undulating ceilings and flowing circulation that guide movement with subtle cues — a kind of spatial choreography in itself. Bauhaus artists made these connections explicit: Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet translated the Bauhaus ethos into performance, merging geometric costumes, modular sets, and abstract gesture. For Schlemmer, the stage was an architectural construct and the body a design element — ideas that paralleled the school’s integration of art, movement, and spatial form.

These cross-pollinations were not just stylistic. They reflected a deeper alignment between two disciplines seeking to redefine human experience in the wake of industrialization. While architects sought new spatial orders based on function and flow, choreographers investigated how the body could be both autonomous and responsive within structured environments. Both disciplines abandoned ornament for process, symmetry for tension, and hierarchy for relational composition — producing spaces and performances that prioritized experience over representation, and motion over monumentality. In doing so, both architecture and dance evolved from representational forms into experiential practices — constructing not only spaces and stages, but new ways of being and moving in the world.

Theoretical Resonances

The convergence of architecture and dance is not only historical or practical — it is also conceptual. At their core, both disciplines grapple with how space is lived, sensed, and embodied. The body is not a passive inhabitant of space but its very measure and medium. Phenomenology, particularly the work of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, offers a foundational lens for understanding this. In Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty emphasizes the corps vécu — the lived body — as the site from which all spatial experience unfolds. Space, in his view, is not abstract or geometric, but perceived through movement, orientation, and tactile relation. We do not observe space from a distance; we dwell in it, navigate it, extend ourselves through it.

This embodied understanding of space resonates deeply with both architecture and dance. For Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa, Merleau-Ponty’s thinking underscores the limitations of a purely visual culture of design. In The Eyes of the Skin, he critiques the ocularcentrism of modern architecture and calls for a multisensory design approach — one that engages touch, sound, gravity, and even smell. Dance, by necessity, already operates in this expanded field: it is a temporal art of breath and friction, of weight and skin, grounded in physical presence. Pallasmaa’s notion of an “empathetic imagination” — the capacity to design with an awareness of the body’s affective and proprioceptive dimensions — parallels how choreographers compose through intuition, resistance, and sensation.

Another crucial bridge is Henri Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis. In this late work, Lefebvre proposed that space is not a container but a product of rhythms: bodily, social, urban, planetary. He described cities as polyrhythmic environments where repetition and difference structure everyday life — the steps of pedestrians, the cycles of light, the tempo of traffic. These insights have been influential not only in architecture and urban studies, but also in choreography.

From the other direction, dance theorist Susan Leigh Foster introduces the notion of the “choreographic imagination” — the idea that movement constructs space through intention, relation, and attention. Choreography, in this sense, is not merely responsive to space but productive of it. The dancer’s body delineates paths, orientations, proximities — turning emptiness into terrain. This idea reframes space as something co-created, relational, and contingent. Architecture, when approached choreographically, similarly becomes an invitation to movement rather than an imposition of order.

Related to this is the concept of kinesthesia — the perception of body movement and position — which is central to both dancers and those who design for bodily experience. Scholars such as Erin Manning emphasize how movement is not something that happens in space, but something that makes space. Her work in Relationscapes positions dance and architecture as allied practices of “evental” becoming — continuous, situated, and emergent.

Together, these theoretical lenses — phenomenology, rhythmanalysis, choreographic imagination, kinesthesia — articulate a shift in architectural thinking from static form to embodied event. They invite architects to think not in terms of objects and boundaries, but of flows, encounters, and temporalities. And they allow dance to be read not only as performance but as spatial research — a way of exploring how humans inhabit and shape the environments they move through.

This perspective extends beyond disciplinary boundaries. If architecture and dance share a common conceptual ground in the lived experience of space, they also intersect in how they question and reconfigure that space. Dance, particularly in its contemporary and site-specific forms, often emerges as a critical spatial practice, one that challenges the politics of visibility, access, and occupation.

Choreographers such as Trisha Brown used the city itself as material. Her Roof Piece (1971), performed across the rooftops of SoHo in New York, reoriented the urban landscape through mirrored gestures, transforming vertical separations into lines of visual and choreographic connection. The performance activated the skyline as a choreographic relay — dancers mimicked each other’s movements from afar, tracing invisible pathways across buildings and air. These rooftop transmissions resonate with post-industrial architectural interventions that expose structure, access, and void. One can draw a parallel with Steven Holl’s Storefront for Art and Architecture, where pivoting panels and an open façade blur the boundary between interior and exterior, inviting a kind of urban choreography not unlike Brown’s spatial logic.

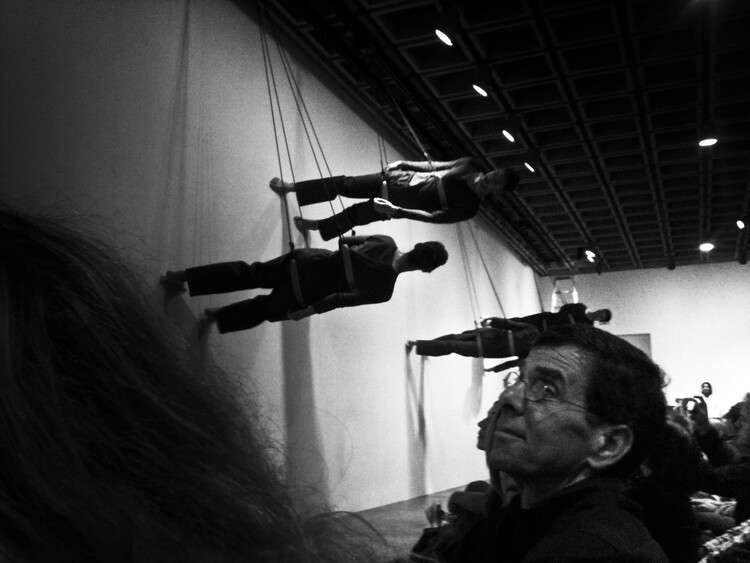

Similarly, Xavier Le Roy’s Retrospective dissolved the separation between viewer and performer within institutional architectures, inviting the audience to walk through slow-moving dancers performing archival fragments, turning museums into spaces of interaction and mutual recognition. This resembles the open white walls of contemporary museums such as SANAA’s New Museum or Tadao Ando’s Contemporary Art Museum in Naoshima; they amplify movement, absorb duration, and stage visibility. Like Le Roy’s use of these spaces reveals the latent performativity of the white cube itself.

By occupying space differently, these projects show that the choreography of bodies can expose, inhabit, and transform architectural conditions — not by altering form, but by shifting meaning. In this sense, dance becomes a form of rhythmanalysis, a counter-mapping of space through gesture and presence. Architecture, in turn, is challenged to respond not as object, but as frame, threshold, and possibility.

Projects in Motion / When Architecture Moves

In recent decades, contemporary dance has increasingly moved beyond the theatre, challenging the boundaries of architecture by turning built space into a site of inquiry, tension, and transformation. Rather than serving as passive scenography, architecture becomes the very material of choreographic research, a system to be inhabited, re-read, or reconfigured.

In Built to Last, Meg Stuart stages bodies against large, inert architectural elements. The performance’s slow, resistive motion against mass recalls the spatial intensity of Peter Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, where the thick, inward walls create a somatic, almost pressurized enclosure. Stuart’s choreography, like Zumthor’s architecture, engages the body not through movement in space, but through space moving onto the body.

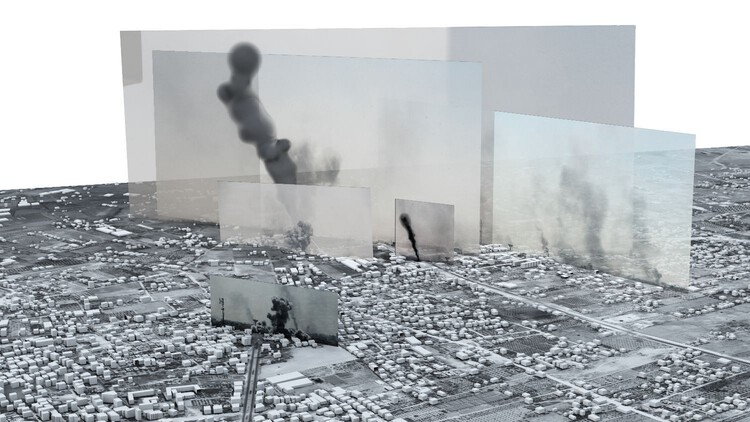

Similarly, contemporary choreographers and spatial practitioners have reclaimed architectures of constraint through embodied presence. Artists such as La Ribot stage performances within institutional ruins or contested sites, using slowness, nudity, and repetition to destabilize the authority of the built environment. In parallel, architectural collectives like Forensic Architecture engage spatial infrastructures as performative devices subverting borders, checkpoints, and surveillance systems through critical mappings and situated interventions. In both fields, the body does not evade architecture but confronts it, tracing new lines of agency precisely where movement is restricted.

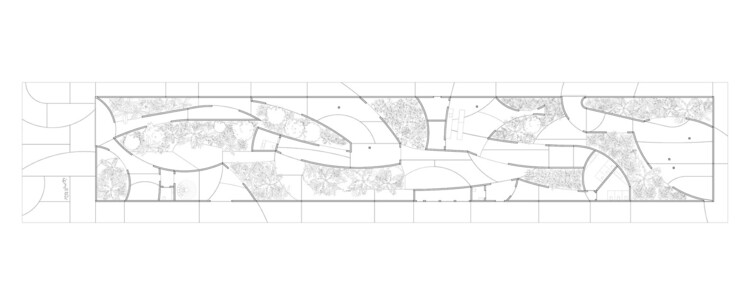

Architecture has begun to respond. Some architects now design with choreographic openness in mind, like Anne Holtrop’s Bahrain Pavilion, where a static envelope works as a spatial proposition — its cast walls curve and misalign, prompting the body to deviate, touch, and pause. Its interior becomes a responsive stage for improvisation. These convergences show that dance is no longer just a user of architecture, but a producer of spatial intelligence. By staging bodies in friction with space — through slowness, weight, repetition, or drift — dance proposes new ways of understanding architecture. It reveals space as lived, porous, and contested.

To choreograph space, then, is to design for relation, not control. It is to treat architecture as an open system, responsive to time, to bodies, and to change. In this expanded field, the architect becomes less a maker of static forms and more a composer of conditions, a facilitator of encounters. Dance, in this context, is more than metaphor. It offers architecture tools to think differently: rhythm instead of repetition, improvisation instead of permanence, attention instead of authority. It reintroduces the body — with its fragility, agency, and politics — into the heart of spatial imagination.

As architecture is increasingly called to act beyond its traditional domains in education, health, ecology, and justice, choreographic thinking offers a way forward. It invites architecture to move: across disciplines, across scales, and across the porous thresholds between built form and lived experience. This, perhaps, is what Architecture Without Limits might look like: not the erasure of boundaries, but their reconfiguration through movement.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Architecture Without Limits: Interdisciplinarity and New Synergies. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.